Raffaele D'Amato

The Varangian Guard 988-1453

Men-at-Arms 459. Oxford: Osprey, 2010. 48pp. $17.95 / £9.99 ISBN: 978-1849081795.

With an academic background on Roman and Byzantine Law, Raffaele D’Amato is also passionate about ancient and medieval warfare. His contributions to Osprey’s series reflect this particular interest. With The Varangian Guard 988-1453, he aims to demonstrate who the men who fought for the glory of Constantinople (or Miklagard, as it was known by Norsemen) actually were. He additionally attempts to explain what brought them to the service of the Byzantine Emperor as mercenaries.

The mythologization of the Varangian Guard as an elite military unit is part of Western popular imagination, as is the case with Norsemen in general. This is to a certain extent the result of successful propaganda by the Byzantine ideologists, but also is cleary often a result of the Varangian’s own military achievements and undisputable loyalty to the Emperor.

D’Amato clearly sets the temporal limits of his analysis. Starting in 988, with the arrival in Constantinople of 6000 Varangian mercenaries provided by Vladimir the Great to the Byzantine Emperor, he ends his analysis with the fall of Constantinople in 1453. He examines the rise of the Varangian Guard as a unit composed of elite soldiers within the complex Byzantine military apparatus. One of the most pertinent questions raised by D’Amato is related to the ethnic origin of these soldiers. The common perception that they all come from the same Scandinavian ethnic stock could not be more erroneous, despite the high number of Norsemen among them. In fact, they were primarily a mixture of Rus’ and Swedish soldiers. The 6000 Varangians arriving in Constantinople from the lands of the Rus’ in 988 were already mercenaries fighting for Vladimir and, at that time, it could be said that they were mostly Scandinavians but also Slavic Rus’. It should be noticed that the name “Varangian” originally referred to those Norsemen, regardless of the diverse origin of the members of the Guard. The end of the eleventh century witnessed the increase of mercenaries coming from Western Europe, especially from the British Isles after the defeat of Harald Sigurdsson, King of Norway (himself a former Varangian Guard) and the victory of William the Bastard (then the Conqueror) at Hastings. Anglo-Saxons and Danes thus became attested members of this unit.

But why did Norsemen, Rus’, Anglo-Saxons and others enter the service of the Byzantine Emperor? D’Amato is very clear about that point: Beyond the merely monetary aspect of this relation, which was very important in that they were very well paid (after all, they were mercenaries), to serve in the Guard became a kind of family tradition for the Scandinavians. This is why men like Harald Sigurdsson, himself a Nordic prince, moved to Miklagard as other great and famous warriors of Scandinavia.

D’Amato also provides a short but lucid history of the Guard which curiously does not extend to his ending date of 1453. Was that due to the lack of information about the Varangians around that date? The question remains open. Other very interesting issues raised by D’Amato refer to the organisation of the Guard, as well as its function as an elite bodyguard regiment, its reputation, and even the unlikely everyday life of its members.

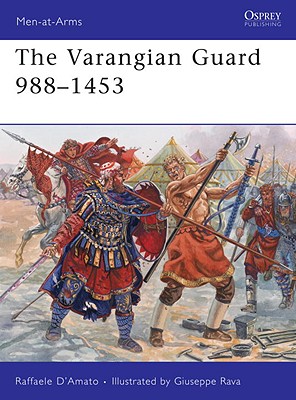

To conclude, the author deals with an important topic, the equipment and weapons of the Guard, and its clothing. As it is usual in Osprey’s series, illustrations are superb. The Varangian Guard is thus represented in all its splendour, from leaders to simple warriors, and from battlefield to ceremonial presentations. D’Amato’s book is very attention-grabbing, even though as Osprey’s series generally are it must be appreciated as a motivating starting point for all of those interested in the Varangian Guard. By focusing on this specific military unit, he indeed makes a noteworthy contribution to his study. Moreover, the selected bibliography is an interesting mix of contemporary sources and recent studies about Byzantine warfare.