Timothy Dawson

Byzantine Cavalryman, c900-1204

Warrior 139 (Osprey, 2009), 64pp. ISBN 978-1846034046.

Dawson’s Osprey booklet on Byzantine cavalry must count as one of the less successful in the series of well-illustrated brief introductions to military history topics. It is not without value, but in some critical ways will be fairly misleading to students new to Byzantine history.

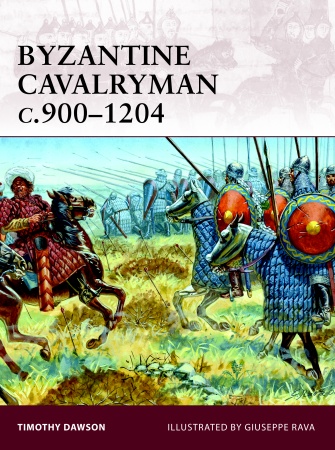

The author is an expert in arms and armor, including reconstructions based on historical exemplars, and on the techniques of individual combat. Thus, the emphasis of the text is on these elements, including detailed examinations of various sorts of armor and weaponry employed by different sorts of Byzantine cavalry. The illustrations follow the same emphasis and complement the text nicely in this way. Therefore, as a handy reference work for the equipment and appearance of Byzantine kataphraktoi, the most heavily armored of Byzantine troopers, and their more lightly protected light cavalry and scouts, the book succeeds.

The problem comes in setting such troops in their wider social, political and even military context. The historical background the author provides on the Empire is, frankly, inadequate. There is insufficient appreciation of the underlying bases for the periodization of Byzantine history, which shows most seriously in the time period covered by the book. While “c.900” is defensible as a rough starting date, it is not in fact carefully defended, and might more appropriately have been pushed back to c.860 and the reign of Basil I, when the first signs of a shift to an offensive strategic outlook are visible in the Empire. This shift stemmed first and foremost from the fragmentation of the Abbasid caliphate, taking the pressure off the beleaguered Empire and allowing it to focus its military efforts more selectively on smaller individual emirates (in the east) and problem points in the Balkans. This is what accounts for the rise of more heavily armored cavalry, the kataphraktoi, as an offensive strike force, over the lighter cavalry that was more suited to the “skirmishing warfare” of the Empire’s defensive period. This shift was accompanied by a steady increase in the role of the tagmata, the full-time professional units of the Byzantine army, centrally maintained and available for offensive campaigning, at the expense of the themata, the provincial militia who had shouldered the burden of defensive operations for centuries. Almost none of this vital background is discussed in the text, leaving “Byzantine cavalry” as an overly broad category of analysis.

Even more problematic is the endpoint of 1204: the disastrous Fourth Crusade. Between 900 and 1204 lay the sea change in imperial fortunes and military organization that followed Manzikert and ten years of civil war which followed, during which almost all continuity with the old Roman army organization that had lasted until then was broken. It therefore strikes this reviewer as highly problematic to lump the Byzantine cavalry forces of the tenth and early eleventh centuries with the much more heterogeneous and differently organized cavalry forces of the Komnenian Empire after 1081. The author notes the rise in foreign mercenary units in the Komnenian army, but then virtually ignores the implications of this in the rest of the text. It is not clear that there was a Byzantine cavalry after 1081, but one must read the text carefully and with foreknowledge to appreciate this.

Other problems include a misunderstanding of mid-tenth century Byzantine politics. The most dynamic and offensively successful reigns of Nikephoras Phokas and John Tzimisces are dismissed as administratively disorganized (which they were not; they were culturally divisive but competent, and administrative issues arose from that cultural division pitting the scribal elite of the capital against the military elite from the provinces). Basil II, who in effect won the ensuing civil war for the scribal elite and brought expansion to an end, is credited with most of the expansion of the Empire.

Finally, there is no mention of perhaps the most distinctive and interesting use of Byzantine cavalry during this period, in the amphibious operations that first failed and then later succeeded in retaking Crete from the Muslims in the mid-900s. Examination of these operations, including specially designed Byzantine horse transport ships, would have given a better appreciation of the professionalism, organization, and tactical flexibility of elite Byzantine cavalry in the period 860-1025.

Thus, except as a reference for arms and armor, readers will be better served by reading histories of Byzantine warfare by John Haldon and more general Byzantine histories by Mark Whittow and Judith Herrin, and the recent editions of Byzantine primary sources that are available, especially Eric McGeer’s Sewing the Dragon’s Teeth.