Konstantin Nossov

The Fortress of Rhodes 1309-1522

Fortress 96 (Osprey, 2010), 64pp. $18.95. 978-1-84603-930-0.

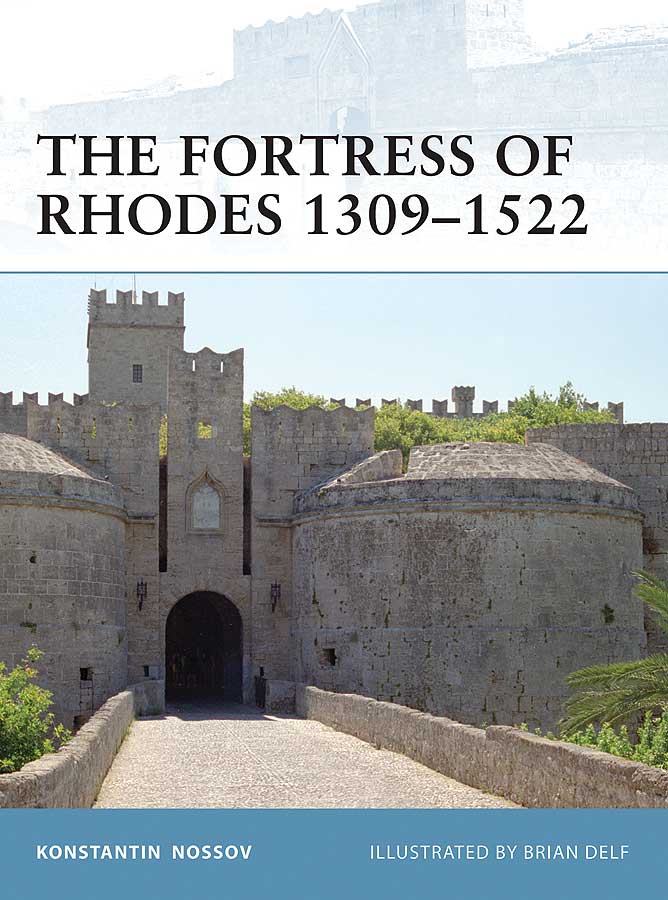

The fortifications of the City of Rhodes are arguably one of the best preserved and most complete set of late medieval defences in all of Europe but have been surprisingly little studied or published. The Knights Hospitaller of the Order of St. John fled Palestine after the fall of Acre in 1291 and, after a troubled period on Cyprus, took control of the island of Rhodes between 1306 and 1309. They took over a city which traced its origins back to 408BC and which still had its Byzantine fortifications. From their base in the city of Rhodes the Hospitallers continued the fight against those they perceived as the enemies of Christianity.

Although the origins of the fortifications of the city go back into antiquity, the present walls are the result of three distinct phases of construction. The first, and largest, dates to the middle decades of the fifteenth century when Grandmasters Fluvian and Lastic gave the walls their current form and extent. They built a tall outer wall with a secondary wall in front of it incorporating small, rectangular towers around the perimeter separate from the main wall and connected by removable wooden ladders or platforms. Outside the wall was a narrow moat and entrance into the city was by a series of fortified gates. The second phase began just before the siege of 1480 when Grandmaster d’Aubusson modified, strengthened and consolidated the defences in readiness for an attack from the Ottoman Turks who were, since their capture of Constantinople in 1453, the predominant force in the eastern Mediterranean. The final, and crucial, phase was between 1480 and 1522 when the walls were radically altered, both to reflect the newest ideas in fortification and to make them ready for a second attack by the Turks—something which the Knights knew would come eventually. It is these changes that are perhaps the most interesting, giving us insights into the way that contemporary thinking to counteract the growing threat of artillery was developing. These changes include the widening of the moat (essentially doubling its width and leaving behind long tenailles parallel to the walls), thickening the walls, providing a wide platform for artillery, and greatly fortifying the city gates. Intriguingly, the walls were also heightened presumably to provide a commanding field of fire over the moat and down the glacis.

Nossov provides a good, short guide to the walls of the city and the two sieges of 1480 and 1522. He divides the book into a number of sections. After a brief introduction and chronology the next section is on the design and development of the walls followed by a section on the principles of defence. He is very traditional in his approach to the history of fortifications and the development of the bastion and these sections should be read with care. For example Nossov states that the Tower of St. George was one of the first fully-fledged bastions whereas this position has been seriously questioned and there is some doubt as to whether it can be described as a bastion at all.[1] He also repeats the story that Tadini had spiral vents dug to counter the Turkish mining of the walls, whereas the original text makes it clear that the vents were just that: vents.[2]

After a verbal tour of the fortress, which can be a little confusing at times, he describes the other Hospitaller building in the city and follows this with short accounts of the two sieges of 1480 and 1522. A glossary is included as is a short bibliography and a list of works for further reading.

This is a very useful work on a subject which really deserves a fuller and more detailed treatment. In fact, the current standard work to which all modern authors must refer was published by Gabriel nearly a century ago.[3] Indeed, most of the drawing of the walls and the ways they were altered over the decades of the later fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries published in the last two or three decades are based on those of Gabriel including those reproduced here. In particular this book can be recommended to those wishing a light and comparatively inexpensive guide to carry round the fortifications.

Notes

1. See for example, Athanassios Migos, “Rhodes: the Knights’ Background,” Fort 18 (1990), and Robert D Smith and Kelly DeVries, Rhodes Besieged: A Story of Cannon, Stone and Men, 1480 to 1522 (forthcoming).

2. The chronicler Bourbon uses the French espirail to describe the countermine leading some modern commentators to interpret these vents as “spiral,” when in fact the word derives from the same Old French root as respirer, souffler or exspirer—all related simply to “breathing”.

3. Albert Gabriel, La Cité de Rhodes, 2 vols (Paris, 1921 and 1923).