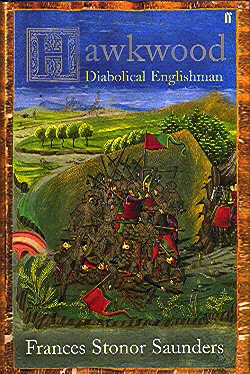

Hawkwood: Diabolical Englishman

It is interesting to note that one of the best known and most studied condottieri of Italian warfare between Middle Ages and Renaissance is a foreigner, from England to be exact. John Hawkwood, who was born in Sible Hedingham, in Essex, in about 1320, was probably the most feared and sought-after condottiere of his age. But what makes him still so famous is perhaps Paolo Uccello's fresco portrait in the cathedral of Florence, showing him on horseback and holding his baton of command. It is symptomatic of Hawkwood's fame that in 2003-2004 two books on him were published. The first (Le armi, I cavalla, l'oro. Giovanni Acuto e I condottieri nell'Italia del Trecento) was written by Duccio Balestracci, an Italian medievalist, the second (Hawkwood: Diabolical Englishman) by Frances Stonor Saunders, former author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War.

Saunder's work, the subject of this review, is brilliantly written, as it often happens with English-speaking historians. Even though Hawkwood's story can be a little hard to follow because of the intricate Italian political situation between XIV and XV century, the author manages to make it pleasant.

Hawkwood's career, that of a soldier of fortune who first fought during the early ages of the Hundred Years' War, and then moved to Italy, where was able to be successful, allows the author to describe this period from many angles. The first chapter, about twenty pages long, tells us how people used to live and die. If the Black Death was devastating, as wars were, this was also, Saunders writes, an era when everything was possible, the age of the renaissance man the 'author of himself'. When Hawkwood arrives in Italy, a whole chapter is given up to the description of the country and its political and military situation. But it is Florence which stands out, with its men, its buildings and its climate, cold in winter and torrid in summer. It is true that the city is the quintessence of Renaissance, but its main role in the book can be easily explained with its relationship with Hawkwood, first enemy and then honoured as a famous son. The pages on domestic life, and on that of Hawkwood we know very little, are fascinating and the imagine of the Englishman and his wife Donnina Visconti wearing night-caps while sleeping, although not based on documents, makes him more human. He could be ruthless and restlessly ambitious, but, Saunders seems to say, he had to protect himself against draughts, like other men.

Contrary to Italian historians, who focus their attention on Hawkwood's role in their country, this book stresses his ties with England. Even though he lived in Italy for decades, in his last years he wanted to go back to Essex for some time. Two of the missives on this planned return to England are the oldest extant letters written in English. We have also to keep in mind that Hawkwood is said to have inspired Chaucher's Knight's Tale. But what strikes the most is Hawkwood's relationship with the English crown. He was much more than a loyal subject, Saunders writes: he was a highly prized agent of Edward III's foreign policy. So, while fighting in Italy, Hawkwood served his country in many ways. For instance, he was appointed Richard II's ambassador to the Roman court (1381) and was again in the English embassy which met Pope Urban VI in Genoa (1385). The crown expressed its gratitude after his death in 1394 by asking the return of his body to England.

Despite being the centre of this book, the Englishman remains in the background. We know much more about his military exploits than his domestic life of his emotions, and the only extant depiction of him to be made during his lifetime is an ink sketch from Giovanni Sercambi's chronicle. But perhaps Saunders sometimes devotes more attention to other characters than to the main one. From time to time Catherine of Siena seems to become the protagonist, making Hawkwood a minor figure. It is true that the juxtaposition of saint and sinner is fascinating, but one would need to have more Hawkwood and less Catherine.

For those interested in military history, Balestracci's work can be more helpful to understand warfare in Hawkwood's age and the organisation of a free company. Saunders explains these sides of mercenaries' activity, but Balestracci is much more detailed. In his book a long chapter (over 60 pages) concern Il mestiere delle armi (The profession of the arms), while Hawkwood: Diabolical Englishman is perhaps much more interested in reconstructing the political and daily environment in which the Essex man lived than in telling his military exploits. For instance, the battle of Castagnaro (1387), in which the Paduan army led by Hawkwood beat the Veronese, is briefly described. Since this is the most glorious among Hawkwood's victories, a longer analysis of it would have been necessary. The massacre of Cesena (1377), one of the most infamous of this time, to which the Englishman took part along with Robert of Geneve's Breton Mercenaries, is the subject of a crude narration, which tries to examine Hawkwood's role in what happened.

The book is accompanied by a series of interesting plates. If some of them are well known, and the aforesaid Paolo Uccello's fresco is one of them, it is to mention a late fourteenth-century sketch by Verones artist showing life in a camp.